THE BEAUTY OF EVERYDAY THINGS by Soetsu Yanagi

(I suggest this is a slow read, paragraph by paragraph across the week)

Recently I read the above book. Although being about Japanese folkcrafts in the mid 20th century, it offers many ideas worth introducing into a discussion of beauty and photography. Having written so many angst filled essays recently, I though it would help me and perhaps others to think for a moment about something more tender.

The author, Yanagi, a lover of Japanese folkcrafts, searching for an appropriate word to describe those naive productions, created this new word In Japanese, in which ‘Min’ means masses and ‘gei’ means craft so ‘mingei’ means ‘the craft of the masses’. For a moment think about today how many people walk around with a camera at the ready in their smart phone. Perhaps there is some equivalent between the original folk arts and this new thing, the folk phone-snap?

This mingei creates common everyday useful things, not made for admiring but for a function. So it can be said that the separation between craft and art is the separation between the practical, to serve a specific function as to hold water, to stir rice, to drink liquid, rather than to contemplate, to appraise, to recognise certain truths which is the job of art. It may also be said that many snaps of the mobile camera are of parties, meals, places one has encountered, an innocent usually artless recording of one’s life.

Another difference is that craft in general is about producing multiple copies of the thing available inexpensively, and art (sculpture, painting) is concerned, in general with the production of one unique piece whose value is in part, based on its rarity. This is of course one of the sick economic rules of capitalism. For instance, when there is hunger through scarcity the price of food is raised.

Yangai laments about the price of works of art in that the ascription of monetary value is meaningless as the value of beauty is that it is valueless, it is beyond money, hence the use of the word ‘priceless’.

According to Yangai, as least in the hinterlands of Japan, folk art originally was unselfconscious and unself-aware whereas for artists and art critics, it must be just the opposite. This is because the craftsperson is asking, how can this thing practically work, how can it work better, what materials can I utilize in my area. Meanwhile the artist is asking about the meanings of life, the nature of beauty and the ways of the world.

Yanagi also talks about the spontaneity of the master craftsperson when they, for instance, decide to depict an image of grasses on the side of a vase. He wrote it would happen in an instant of spontaneity often leading to beauty. This he said was consistent with a Buddhist idea ‘to awaken the mind without fixing it anywhere’. Often when I have asked people why they released the shutter (shot the picture) at that moment, for instance of a landscape, they reply by saying “oh, it was kind’a random”. But I don’t think it is random or as Yangai quoted that ‘the mind was not fixed’. The individual’s entire history of experiences, culture, education, memories are working beneath consciousness to say ‘now’. Part of the struggle to become a photographer is to make conscience and understand these assumptions, prejudices, attitudes, to truly see.

Yangai addresses the unity of beauty with what he refers to as pattern. I only understand this when I consider pattern to mean the use of form and form as a part of composition. To my mind form is meaningless in photography without its use in representing the photograph’s content or narrative in the clearest and most enticing manner. It is from this unity of form and content that the viewer is touched by the message or meaning of the image. Concentration on form without content is decadent and on content without form is talentless scribbling.

All photographs are made of three elements: form, content and technique. Technique is the artisanal craftsperson’s contribution to the work, content is the storytelling, philosophical contribution and form is the creative artist’s contribution.

This also gives rise to another quality which is the appropriateness of form for the content (sometimes referred to as style – but that is for another essay). A photograph intended to be a tender image of a child, printed in a harsh high contrast black and white would be contradictory to the gentle loving image one imagines in which tones and colours would softly blend one to another. The high contrast is an inappropriate use of form (and technique) in relation to the narrative of the image. These are not hard and fast rules; perhaps in a different context the use of a contradictory look/style would be appropriate…this is a creative judgement which defines the overall visual poetry of the image.

Again paraphrasing Yangai, form is at the heart of a work and an expression of its most profound nature. The more relevant the form is to the content, the more it captures and represents the nature of the content’s life. Form is the essence of beauty, whereas content announces its meaning, its truths. Think of a song’s lyrics, melodies and rhythms which may carry memory and meaning sung by a person capable of expressing those things. Now think of it sung flatly, with no commitment and by a poorly produced voice. No matter the inherent beauty of the song, its formal delivery ruins it.

Below is a picture of a cabbage leaf, largely lit from behind revealing its basic structure, its cardiovascular system. I believe that the photo goes some way in complimenting the beauty of nature. The same leaf could have been photographed in 101 different ways, against a different background, in different lighting conditions, with a different framing (smaller, larger in frame, or closer, further) but for me, this was obviously a solution.

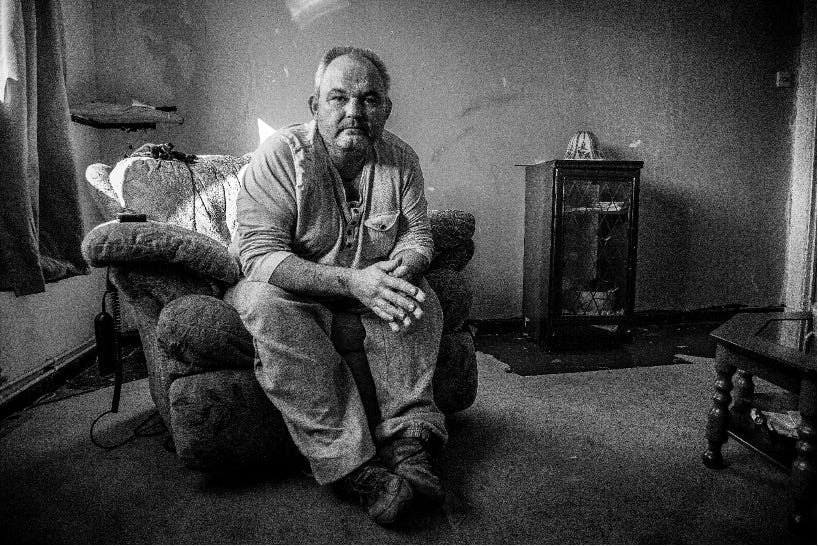

This then opens another idea, that the use of appropriate form accentuates the meaning of an image. No longer is it just another cabbage leaf. Photographed and printed carefully, it makes this leaf special, it accentuates its existence. This idea is always central to the portraits I make to accentuate the specialness, uniqueness, the being, the troubles, loves, worldview of the sitter. This is about appreciating that they occupy a serious and perhaps troubled private view that affects their skin, their set of mouth, their emotional truths via their eyes. Someone once said that a person’s face is a roadmap of their lives.

Beautiful appropriate form, this enunciation of content opens the audience to relevant truths, to dreams and hope. This is its power, which is the power of art. The important thing about this, especially for photographers and film-makers is that often we do not control the environment or the events we are in, but one must none the less strive first though the lens and then in editing the image, to have all which is relevant to the narrative inside the frame, and all which is inessential outside the frame. It something is inessential in the negative, one can use print manipulation, as below, to diminish its presence.

For art to be understood by the audience as being beautiful as opposed to pretty or entertaining, it must offer truths meaningful to people at that moment in history. When one speaks of handicrafts, their value is in their utility or usefulness in the day-by-day world. For art it is different in that its utility is more of a philosophical, emotional and spiritual need. Why am I here? What is the goal of life? Do I have a debt to anyone in terms of my existence? Is my moral compass well adjusted? Do I hold values I am proud of? What can I hope for?

When I compare what I have seen in Japan with my Anglo-American background, I sense refinement against corporate produced cultural vulgarity, I see the respect for beauty rather than the neoliberal consumerist attitude that anything can be purchased and binned without remorse, I see the ability and desire to view into the underlying meaning of things rather than just the trending newness of things, and I can see the honouring of one’s past family rather than the lachrymose Hallmark cards sentimentality. Further, the trendy post-modern movement of the Thatcher era reduced all knowledge and skills to the same level, which implied what was a false idea about democracy, but served to undermine the authority of excellence and knowledge. All that Japanese preciousness needs to enter the serious photographer’s paradigm of making.

Yangai speaks of natural beauty, the beauty of everyday life, which he blends into egoless freedom. Although I have read bits about Zen, I am neither an expert nor a practitioner, but I think there is something splendid in this idea that we can attempt to innocently see that which is beautiful around us. When I think about what is happening in Gaza and Ukraine (and the other 30 war zones that now exist) I imagine people see the beauty of the human soul in others sacrificial attendance (as Medicine Without Borders), and the help and sacrifices many people offer at this horrible time. But for us lucky enough not to be there and perhaps lucky enough not to be in poverty, we can see beauty as light falls across a bowl of doughnut nectarines and appreciate it for its simplicity and naturalness.

This asks the question about how one sees. I want to make a distinction between one’s eyes able to see and one’s soul able to look. Often there is an impurity in this, that one reduces the world to sets of dualities: he is a Muslim so he must be bad, she wears too few clothes so she must be a slut, etc. Many things intercede between seeing and looking: lack of curiosity, imposition of intellectual and especially ideological constructs, one’s long time belief system which asks the question, ‘why do you believe what you believe to be true is true?

The world becomes far more interesting when you throw all of that off and begin to appreciate a purer way of seeing via the more troubling process of looking: asking questions, reprimanding yourself when you jump to your old, long established assumption and when you rely only upon emotional responses without engaging critical thought. Some will argue that they use their intuition, which is all they really trust. But what is that built upon other than a history of one’s experiences and how one has come to judge them.

As a long time practicing photographer, it’s my wish to see what is real and profound in others rather than using the subject to prove a hunch of mine. In other words, I try to keep my ego behind the camera. One of the ways one can do this in documentary work is by respecting other people’s lives and by being serious with them. This is when the photographer can cross a bridge of differences and for a moment share a sense of togetherness or oneness with another because they know they are being respected and thus I become invisible.

Often when I have taught people about photography they ask what can I do, how can I find things to photograph. The fulsome answer can be found in part here but one thing I suggest if they wish to practice documentary work is to offer their skills for free to a local charity. The confrontation with reality, with people struggling, with noble ideas and how they can viably use images in support of an idea or cause is a big challenge, but it offers a steep learning curve and deep satisfaction.

In all the above, remember the name of the medium ‘photography’ means ‘designing with light’. Yes, content is central to the image but nothing means anything in photography without the beauty of light; that is the essential element of form.

This is from Tina Ellen Lee, with whom I work on projects.

A year ago we started an online network with Ukrainian and British Artists and Academics to see what we could do to help.

This has turned into a collaborative training programme for trauma informed care across Ukraine; to develop a Creative Arts Trauma Informed Curriculum with qualification adaptable to many professions.

We have a meeting of 20 Ukrainian and British Artists in Warsaw at the beginning of February to work together to develop this training. We had raised all of the funding, when 5 more academics and artists asked to join the team. We aim to cover these costs by raising a further £2000.

Please see this.

At a time when the larger issues are overwhelming, to be carefully guided through a particular concept or theory with beauty and thoughtfulness is balm to the soul. Will read again. Thank you

Thank you so much, Robert. I've been weighing these questions precisely.