This week I’ve written a speech and am delivering it

to the annual meeting of the Southwest Multicultural Association

about Multiculturalism and its embrace of the achievements

engaged within Black Culture Month.

I may have been asked to speak as my exhibition,

SEARCHING FOR THE MOTHERLAND,

about the post- Empire Windrush generation’s life in the UK

is just down the street from Dorchester’s Corn Exchange

where the Association’s meeting will occur.

Being asked to speak was a surprise and a pleasure,

but I did ask myself, ‘why me’?

The psychoanalyst Karl Jung wrote,

“to discover oneself, one must be willing to ask questions.

One must be truly curious.”

He also wrote, “the first question must be,

“What is the first question I must ask”?

For me as a younger person, it became, ‘why photograph?’

In the process of answering this,

I began to realize how much injustice there was to photograph.

It also led me to recognize things I cared about

and therefore I began to see underlying themes in my work,

themes I wished to develop.

Eventually I began to understand those themes

were a reflection of my moral concerns.

They can be summed up as my disquiet with poverty,

ignorance, poor educations, corrupted cultures, destruction of the planet,

lack of true democracy and lack of freedom,

lack of justice, of truth, of equality (especially under the law)

and lack of kindness.

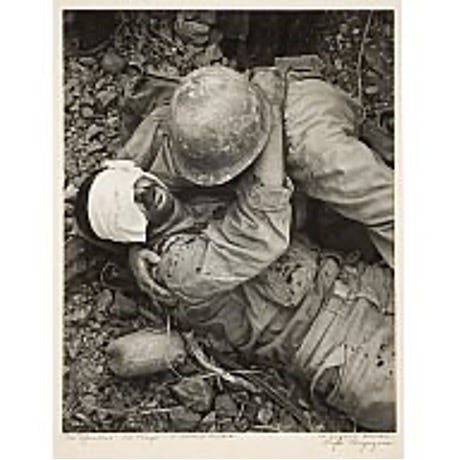

My first memory of deciding I wanted to be a photojournalist

was when looking at photographs in LIFE magazine

from the War in the South Pacific by W. Eugene Smith.

I imagined that I too could travel the world,

exposing bad things,

naively believing that to do so would help others

understand and then right the wrongs I would reveal.

Whatever my motivations were,

the answers to ‘why photograph’

were linked to what content I was drawn to explore.

Caring about something leads to one’s themes.

For these themes to be photographed

there must be specific subject matter

which embodies of represents the theme.

To create a story out of this,

the photographer needs to choose what can be photographed.

I try to become aware, without judgement,

of the qualities of people, places, things and events.

For whatever limitations of youthful testosterone and ego,

I struggled to be able to see more and appreciate more.

The older I get, the more aware I become of the complex and rich universe

within which I live,

and there seems to be so much more to encounter

and to tell stories about,

so the ‘why photograph’ and the ‘what to photograph’

lead to the ‘how’.

The how, is a question of STYLE but also of morality.

STYLE can be defined as, “the visual appearance of a work of art

that relates it to the mood of the subject’s inner condition.

When we encounter a photograph,

consciously or not

we often first notice three elements:

*what is its subject matter, (for instance an old man on a bench)

*what is the subject matter’s story, (he is alone, perhaps sad, depressed,

perhaps poor)

*and does the look of the photograph (its style)

reflect the inner reality of the subject?

Is it too bright or too dark?

Is it too colourful or too colourless?

Is it too sharp of too diffused?

Is it a wide, mid or close up composition

and how does the difference of the subjects size in the frame

reflect his inner condition?

Style is a window onto a specific organisation of form,

or it may be referred to as ‘a look’.

The nature of style can be defined by the way in which form is used:

is it fanciful, romantic, mythical, realistic, naturalistic, decorative

and are those elements consistent

with the viewer’s sense of the subjects condition?

These are things that most people are not trained to analyse,

but none the they may sense and feel contradictions.

Whatever the nature,

style cannot be disunited from its fundamental origins,

the world view of those groups or classes of society

from which the style arises

and by whom it is sponsored and whom it represents

all filtered thought the photographer’s own origins.

The use of technique to alter the appearance of an image

is the conscious or unconscious imposition of the maker’s world view.

It is here the viewer must pause to reflect

that there is nothing objective about the image.

It has been altered or mediated

(hence the word ‘media’ meaning the transformation of one thing into another)

by the imposition of an photographer’s tastes, prejudices, fancies or needs.

I try to correlate what I produce as a finished image

with what I imagine is the inner truth of the subject matter.

This is not about ensuring that the image

simply shows clearly the outer reality of the subject

but rather how it reflects the inner meaning of their existence.

W Eugene Smith, one of my photographic heroes, was clear about this problem.

He fought against his editors because he saw

“a whole world view (his) being substituted by another world view (the editor’s)”.

He struggled against this editorial control his whole career.

So have I.