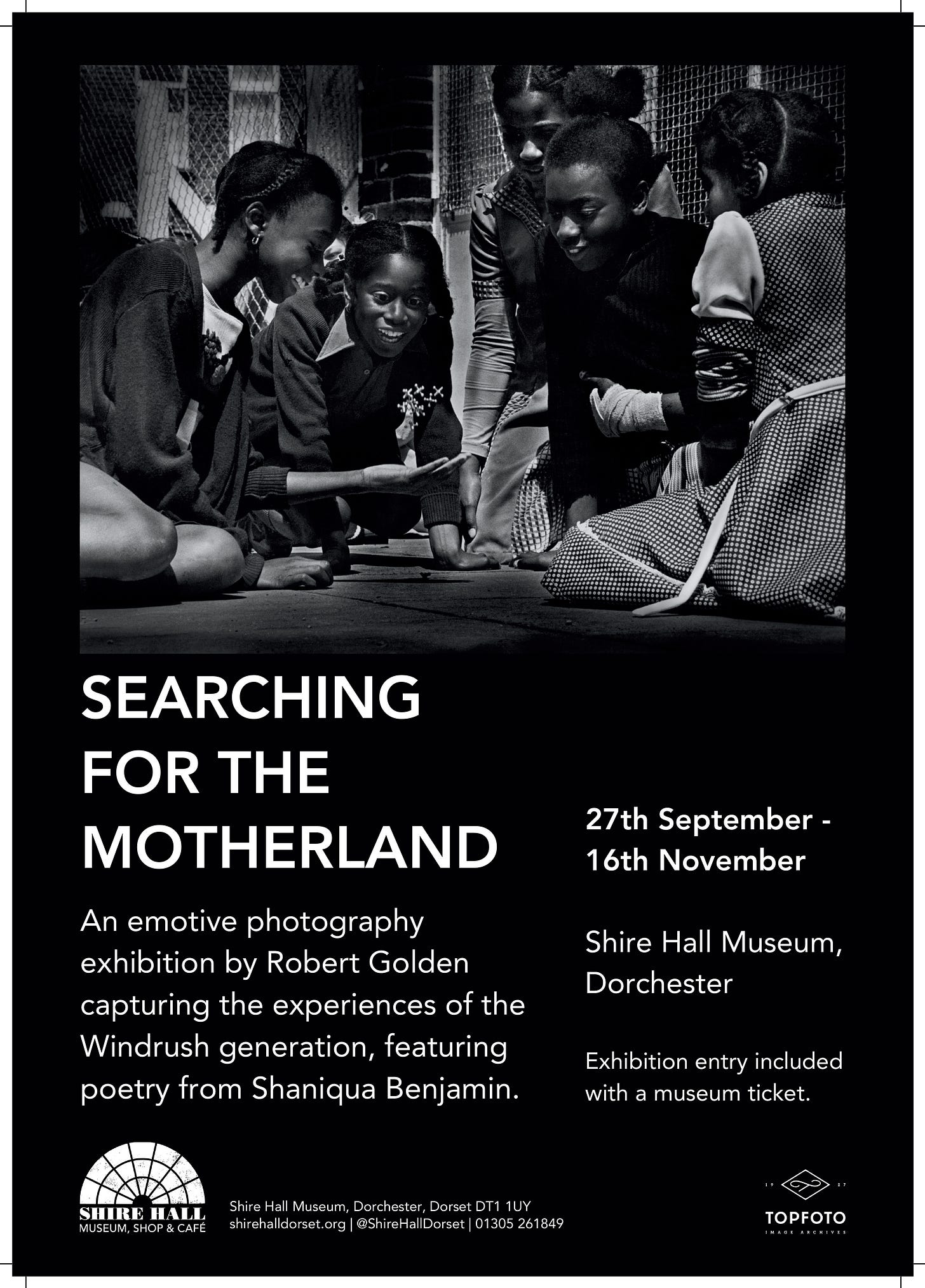

Opera and cinema are hot media which wash over you.

Photography is a cool medium which you must go to

asking ‘why did the photographer shoot this image at this time?

What did the photographer think was important enough to preserve for ever?’

Further looking and you may see that there is a subtext,

an underlying meaning that begins to shine out as you move from image to image. You come to recognise that all the pictures play their part in creating a metaphor: that there is hope or danger or a common humanity to be shared.

That the surface of the images,

the subject matter doing or being this or that

is playing a role in revealing underlying meaning.

***

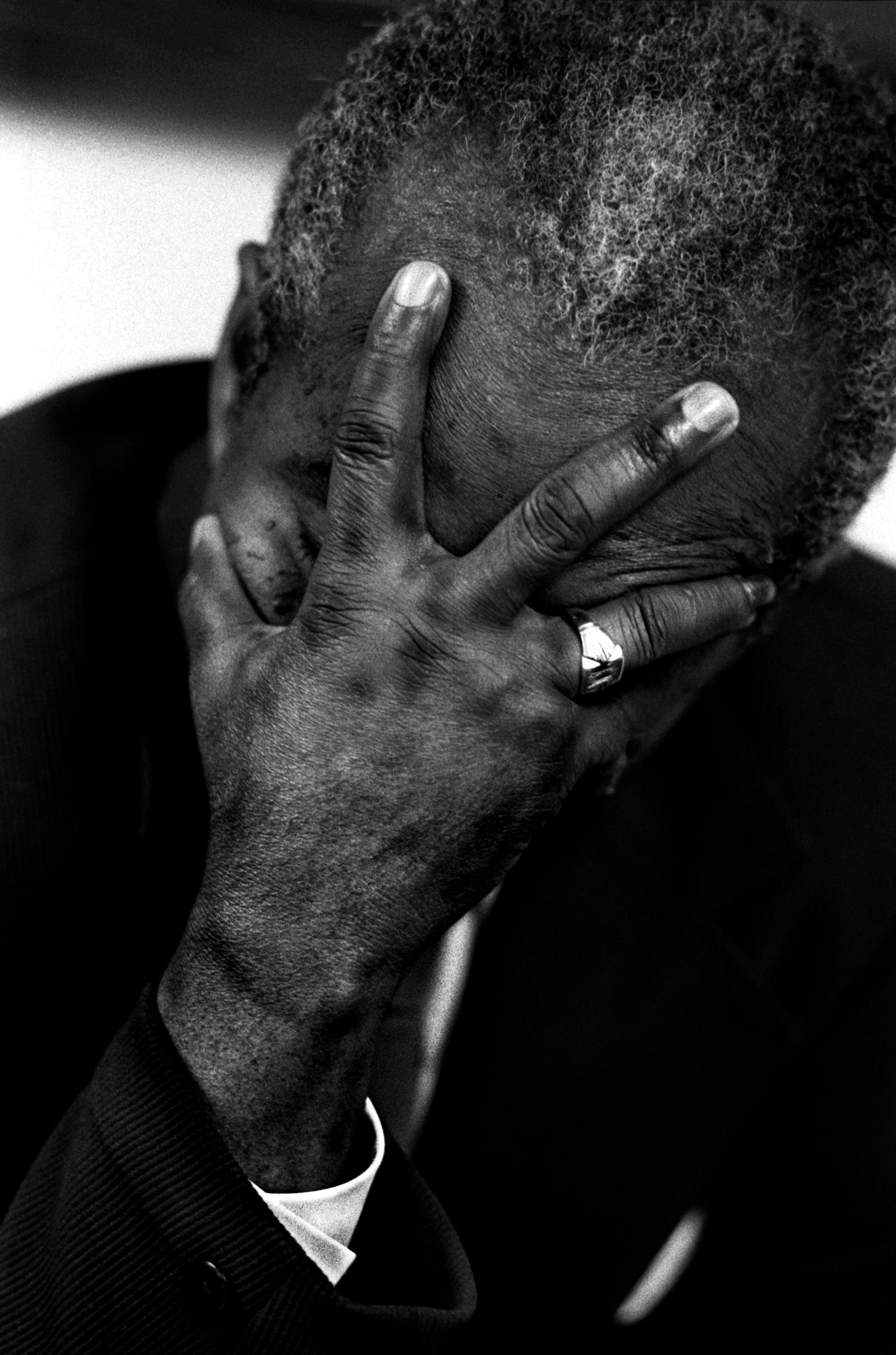

These photographs were made throughout the 1970s,

beginning about 25 years after the arrival of the Empire Windrush generation.

The older people in the pictures,

some of whom are amongst the original group,

can be seen responding to social, cultural and economic conditions,

perhaps as any group of migrants or strangers in a strange land

have forever responded.

In their home islands the UK dispossessed them of their freedoms

and their economic survival;

in the UK they were dispossessed through rejection, arbitrary racism,

harassment by the public, the police, by bureaucrats, landlords and politicians, and condemned as ‘Other’.

They had imagined a life in a cold, distant land being better for them

and for their children than living in what was too often

an economic and cultural dead-end on the island domains

left impoverished once the value of tobacco, sugarcane and cotton dropped

and the strategic value of the islands no longer existed for the British Empire.

***

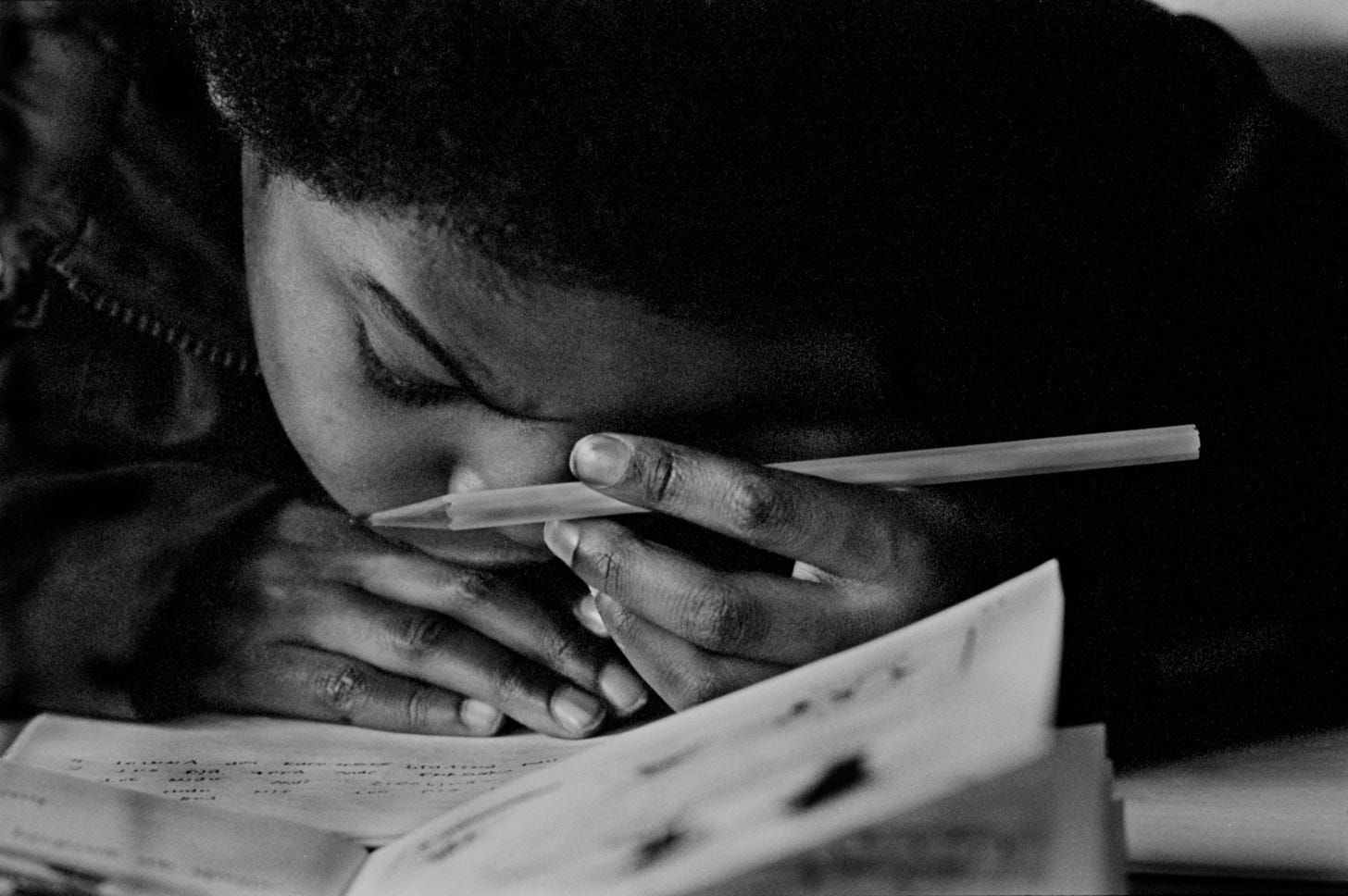

Their children were even more harassed,

finding less solace in the church and in the hostile population

of the so-called Motherland.

‘So-called’ because in mythologies,

Mothers embraces their children and cares for them.

She is of the earth and nurtures the children physically and cares for their souls.

The Empire generation’s children, suffering

discrimination, harassment and with fewer opportunities,

with their potential and abilities ignored because of skin pigmentation,

remained exiles in England,

cast out from their mother’s embrace.

Some revolted, finding a voice in race and class based ideologies.

Others turned their backs as best they could on the dominant culture

and attempted to forge their own way,

some in desperation were tragically criminalized,

but others, against the odds, succeeded culturally,

educationally and professionally.

***

How did I, a young white foreign photojournalist become accepted?

Previously I played a part in the American Civil Rights Movement

and in the anti-Vietnam War struggles.

When I moved to London from New York

I became engaged in the Right To Work Campaigns and the anti-Nazi campaigns as a photographer/designer and as a participant.

In brief and for reasons of my own history, upbringing, self-education

and my studying history,

not only did I find racism and nationalism emotionally unacceptable,

but intellectually hollow and morally repugnant.

I found people I met in the black communities, warm, friendly and accepting.

•••

Look at these images.

Look closely.

What you may see, if you spend time,

is what state of mind individuals were in at that moment of being photographed

in that place, illuminated by that light.

What you can see is that I was either invisible or accepted

because the people in the pictures sensed I was to be trusted.

At best they liked me; at worse they simply ‘paid me no mind’.

These pictures are about creating image equivalents to my underlying

always evolving story:

that too many human beings are in struggle against economic,

bureaucratic and political bullies,

and that many of those in struggle possess dignity and untold strengths,

even as they are forced to carry unacceptable burdens, they do so with grace and modesty; both worthy of embracing, celebrating and admiring.

For more information about this

For more information about Robert