1

The audience see my pictures of everyday life.

They may unknowingly become captivated

by the simplicity of the subject matter:

a man crying, a child grasping a piano, an angry boy speaking out,

men and boys marching through streets with a sign demanding,

’when is this going to end’,

musicians laughing from their depths.

Perhaps the audience wonder what is happening to themselves

as they view the images?

They begin to see that hands,

facial features and their emotional expressions,

a presence of rough skin, swollen muscles, eyes lost in unexplainable grief,

and distressed actions claw their way out of dark backgrounds,

seeking illumination, seeking brighter tones,

seeking to be shadows but not dark and empty blackened pits.

Poor light struggling through windows,

light fainting from strip fixtures,

bruised light falling off a broken wall.

In these underlit images, the film is pushed to its limits of recording:

underlit means underexposed and over processed to at least cajole

the low mid-tones to form sufficient density on the negative

offering some sense of surface, space and materiality.

2

I have rescued a few moments out of the darkness:

a youth stares into my camera

struck by a circle of light in the busy market,

children play under dim buzzing fluorescents,

and on a dingy afternoon, in which the fat clouds

scrap the tops of pork pie hats and Bry-nylon headscarves,

men ogle manikin worn clothes they can only dream of owning.

But these are not what the pictures are about.

Early in the 20th century, the Russian painter Kandinsky wrote:

"Judgement must be passed,

not on the [painter’s] failure to achieve "naturalism"

but on the failure to express the inner meaning."

(from "Concerning the Spiritual in Art" by Wassily Kandinsky)

By ‘naturalism’ he meant ‘accurate descriptions

of the external appearance of things’.

Yes, what is important is not the subject matter being described

in startlingly pellucid light

but the inner meaning of all the 53 photographs together.

That is something precious, something humane that embraces

the relationships between relevance, meaning, truth and beauty.

My photographs are 50 to 55 years old.

No one has said to me, “why these are old pictures”.

I believe that is because their inner meaning is as relevant now

as it was back then.

Which is what?

That the people photographed and I held each other,

not physically but in some nonreligious sense, spiritually.

They recognised that I was okay

and that I saw them as three dimensional individuals

struggling through life in a hostile, antagonistic world.

I did not see them as types,

as manifestations of a race, of poverty, of whatever

They knew I knew, and I knew they knew I knew.

This special essence of picture making I sought:

that the underlying values of the images embodied

- via the specific subject matter -

a set of recognisable and relevant people, things, actions and events

which appeared to be offering some truths about their lives.

Those revelations touch people’s hearts because they are universal.

3

In this case it was that some young white guy from another culture and country

could enter a community, somehow befriend and become trusted

to witness the heartfelt struggle of people’s day-by-day existence,

and cared about them as if they were family.

That is where the audience embraces truths

that have them exclaim aloud or silently, “this is beautiful”.

And of course that was and is the reality,

that we are family as in THE FAMILY OF MAN,

the book that profoundly touched me as a young teenager,

the book that helped confirm for me that racism made no sense,

that differences were fascinating, enriching, and full of pleasure.

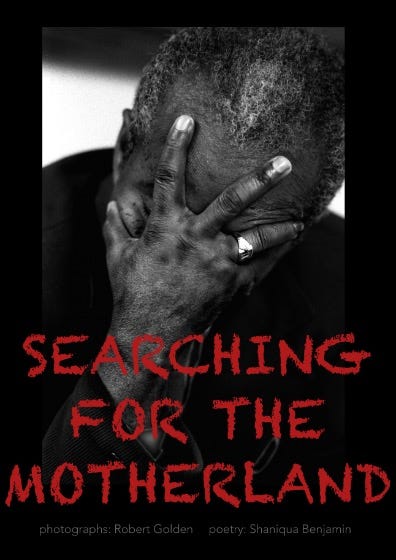

I suspect that to the surprise of the people who view

SEARCHING FOR THE MOTHERLAND

many of them have recognised the underlying humane meanings

of the images and the collection and their organization on the walls,

helped by the wonderful poems of my friend Shaniqua Benjamin,

as this one below.

Who will tell our story?

Of generation to generation,

rituals passed down by our lives

even if you never hear us speak,

our voices immortalised by who cared

to look at the deepest sense of who,

not what we do or how

we were labelled in our quest of

what to gain here?

You can see here a 2 minute short about the exhibition.