LEARNING TO LOOK

ways to understand the inner reality of people and events

In teaching photography and film

early on I talk about learning not just to see, but to look,

to recognise that reality is not to be found on the surface of things.

A part of my ability to look is based in the essays I have read.

I wrote last week that this week I’d tell you about the writers who have helped to form my intellectual and aesthetic ideas.

That means about those who have guided me with the wisdom

I could embrace from their books,

which has helped me as a photographer and film-maker, and as a human being.

They are novelists, poets, philosophers, art critics and commentators and more.

This week I’m writing about two people whose essays about art and society,

art and politics, art and history have broadened my understanding of the world.

What I mean by ‘broadened’ is that they have opened my eyes

to greater social, psychological,

and (in a none-religious context) spiritual ways of thinking.

I read with a pencil in my hand,

making thin marks next to paragraphs.

Occasionally I write an observation in the margin that has occurred at the time.

Once finished reading the book, I return to it

and either copy out what I have marked up

or often find myself writing pages stimulated by the word, line, sentence, paragraph.

For me, this has always been like having a dialogue with these brilliant people.

Both of these men were Marxists who flirted with Soviet communism.

Many of the ways of viewing the world via Marxist analysis work for me,

make more sense of the world than do social democrats and right wing views.

But I have been to a number of communist and ex-communist countries

and have no admiration for the lack of democracy and opportunity

nor for the strict control of art and artists.

Too many fine poets, playwrights, and visual artists have been isolated, ignored

or destroyed by their regimes.

Marxism is a way of looking at the world.

Communism always seems to be an oppressive political system.

Marxism offers an analysis of art and society rooted in economics and power,

out of which grow the culture and therefor the artist in any given period and place.

For instance, the extraordinary rise of artistic brilliance in 15th century Central Italy

has been a rich source of delight and knowledge for me.

That humanism*arose out of the ashes of the classical world,

rediscovered after 700 years of religious and aristocratic stagnation and oppression.

These two Marxist intellectuals break that down

and open it to the same question over and over: ‘why?’

That is the beauty of Marxist intellectual tools;

they establish an inquiry that must be answered at least in part by material reality

or rather, how people live their lives.

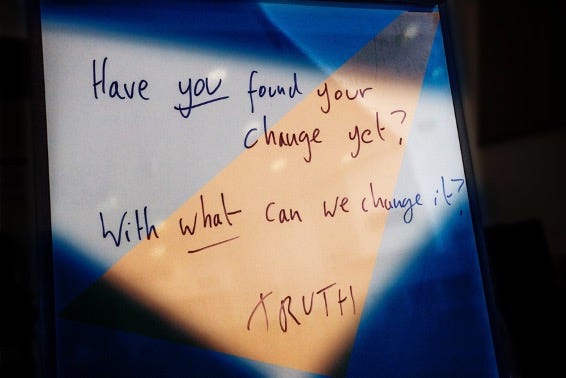

Why did change happen?

What was different that prompted the change?

How did individuals and society change?

Why did change happen when it did?

The first writer to mention is György Lukács (13 April 1885 – 4 June 1971).

He was a Hungarian Marxist critic, historian and philosopher

and one of the founders of Western Marxism

which believed orthodox Soviet Marxism was unsuitable in the West.

In 1923, Lukács' published essays called HISTORY AND CLASS CONSCIOUSNESS which helped define his ideas about literature, art and culture

in a progressive Western society.

There are many ideas which he introduced in his writing.

What struck me most was the idea that Western artists and writers

were so much more concerned with their own lives than with the world around them.

I had always reacted against the idea

that I would find more peace within myself

and a greater understanding of my place in society

through being psychoanalysed.

I had and still have a negative reaction to family psychodramas,

to self-involved characters, and to art for art’s sake**

which always seemed a simple way for the status quo to celebrate an art

consumed by formal concerns (as colour or materials)

and unconcerned with the nature of society or the profound problems of life.

For me history, tells a more precise story of our lives than psychology,

although I admire much of what I have read of Carl Jung.

Arthur Miller’s play A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE is a prime example

of merging the private agonies of an individual with the surrounding society.

Where the individual’s needs or wants meet social needs or norms

is the greatest point of conflict

and therefore the greatest point of tension.

Lukács also honed the theory of ‘class consciousness’ –

the difference between the objective reality of a class

and that class's subjective view of itself.

As a documentarist, this perception proved invaluable,

providing me another lens to look at that which I found around me.

In the nineteen seventies when, across several years,

I photographed the demise of the English industrial working class,

I understood that I, as a foreigner,

would never understand fully the inner lives of the people.

I had grown up with different music and stories, traditions and dreams

but I could at least understand their individual and collective relationship

to the world of culture, power and money which surrounded them.

This was in part, because of having previously read Lukács,

Central European leftist intellectualism seemed to make sense to me.

Second I want to mention Herbert Marcuse (July 19, 1898 – July 29, 1979)

who was a German-American philosopher, social critic and political theorist,

associated with the Frankfurt School*** of critical theory.

He was one of the first to articulate

that modern technology was used as a repressive mechanism

against the mass of people

in capitalist and communist societies.

The Western working and middle classes were incapable of objectifying their lives.

because of the imposition of an oppressive and pervasive culture

via these new mechanisms of technology (radio and then TV).

In his book, ONE DIMENSIONAL MAN he outlined how these cultural mechanisms

reduce people to uncritical one-dimensional thinking

which trains them into not questioning the imposition of choices,

attitudes and social habits

that trapped them into subservient intellectual, spiritual and economic roles.

He helped me to question

how it is that the broad mass of educated middle and working class people

in the West were and are incapable of seeing and responding to their oppression.

Is it that they wish to mimic their masters

because they wish to live the same wealthy life style?

Is it because they don’t care enough about what, for instance,

climate change will do to their children’s lives?

Is it because they have lost whatever critical intellectual facilities they once had?

Is it because they are lazy, bought off, uncaring?

In all of this I say to myself, it is hard to rebel,

or simply to question in particular

when the rebellion is generally against an unseen enemy,

an abstraction?

But I ask myself, ‘where is their moral compass?’

I find only silence?

Marcuse’s ONE DIMENSIONAL MAN goes part way in offering understanding.

I continue to research, to read and to try to gain wisdom and will share what I have learned from others in the next few essays…..