REFLECTION

In the last two weeks

I’ve written about two of the thoughts which lead from Democracy to Kindness.

Based on responses it seems to me that readers were not particularly interested.

For me this is distressing in that one of the reasons I write, week-by-week,

is that I have had the luck to be able to read across the last decade

a substantial amount of books, essays and articles

about the politics, economics, cultural and social issues

which dominate our lives.

Because the reality of these things is befogged by the media’s smoke and mirrors,

it is difficult to see how we are exploited by the dominant neoliberal ideology

that runs every moment of our lives.

For me, this privilege of learning needs to be shared.

A TREAT

As a relief from those previous two essays

I’m going to tell you about an extraordinary exhibition.

I visited the Courtauld Gallery in Sommerset House last week to see an exhibition

that had been highly recommended to me.

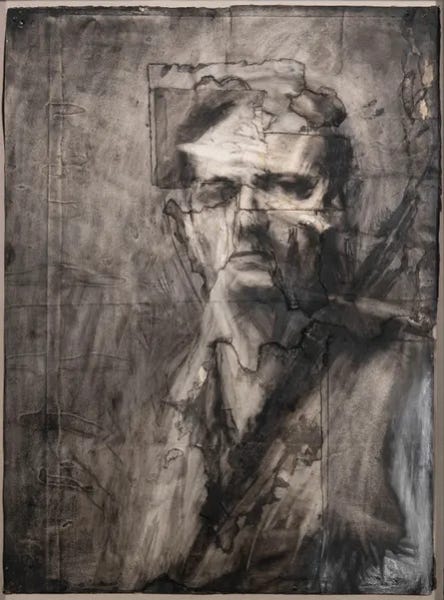

It consists of a small group of large charcoal portraits and several painted portraits

by the British painter, Frank Auerbach.

The exhibition was small but totally enveloping and mesmerizing.

After having walked around the exhibition

I sat on a bench and stared at the paintings one by one,

asking myself, ‘what am I seeing that is so compelling’?

How has Auerbach seduced me into this trance?

Why have I found it difficult to look away?

Each image had been worked and reworked,

drawn, smudged, erased and redrawn.

In some cases the paper had ripped,

perhaps as a result of the erasing and reworking,

and in some cases perhaps Auerbach had cut and pasted.

I realised that I was seeing multiple realities

in the multitude layers of studies overlaying each other.

They embody the complexity of his sitter’s

layers of differing truths and being.

There is nothing romantic in these portraits.

They are tough and visually often harsh,

but there is immense tenderness

even in the shadows of the erasure smudges, rips and layered repairs.

Auerbach was revealing the rich complexity of human nature.

He drew and painted the same few people

over and over across more than a decade beginning in the early 1950’s.

In their tenderness but insistence to reveal truthful conditions or states of being

his explorations surpassed conflicts and contradictions in time

which dissolved as I continue to investigate the drawings.

It was as though investigating, layer by layer, an archaeological site.

I began to recognise the love Auerbach had for each sitter.

Other painters, from the Renaissance on have honoured,

complimented, desired, pleased their sitters,

but I think it is rare that the viewer sees deep caring and love

as in these images.

It is rare, special and part of the engagement with the work.

I purchased the book of the exhibition

and have looked again and again at these powerful images.

Purposely though I have not read the texts yet as I wanted to write with fresh eyes,

with my photographer’s eyes

which have been commissioned to make many portraits,

and having my own history of developing an approach to portraiture.

Sitting on the bench, looking at the images,

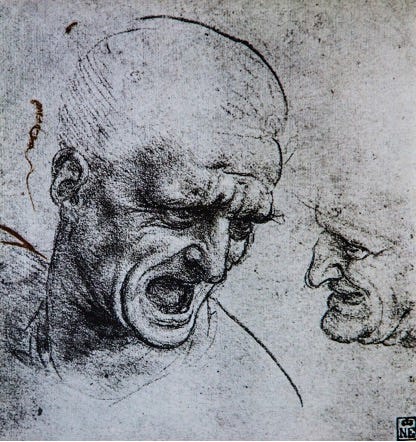

I began to have memories of Da Vinci’s drawings of children, adults,

and of fine looking or distorted humans.

Glancing back at Auerbach’s images it was as if seeing Da Vinci on steroids.

Many of Da Vinci’s drawing studies are more complete,

more finished and reveal a regard for different human types,

as in the study below.

Whilst being compelling and in many cases beautiful,

they also ring of social and biological inquiry:

Da Vinci was exploring what it was that created individuals,

in so doing, escaping from the narrow moral restrictions of the church

with its insistence that human beings were neither individual

nor of a specific personal and private character

but only reflections of their God.

In art, as opposed to reportage, content is abstracted,

estranged and mediated in the name of deeper realities.

As aesthetic form becomes content

it creates a more profound truth

– one which is antithetical to superficial description standing in for truth

(as so often photographic portraits are)

and one which is threatening to established truths.

I suspect that Auerbach asked himself over and over,

‘what is it that troubles the roots of my being

and how, at those roots, the concepts of the world and myself

have been manipulated and indeed stunted by conventions’

which, in his modest way, he rebelled against.

If Auerbach had been affected by Da Vinci’s portraits,

I suggest he was affected by Caravaggio

who also was influenced by Da Vinci.

There are three key features in Caravaggio’s work that are in Auerbach’s.

•The first is painting the subject as if illuminated by single source lighting,

the dramatic moulding light and shadow on each head

which gives roundness, solidity and pulls the subject out of the gloom.

•The second is that the shadows, as in Caravaggio’s paintings,

are filled with portent

as though the darkness has as much a claim on the sitter as the light.

•The third is that he used humble street people as his subjects

rather than the rich nobs who were used to appearing in paintings for alter pieces or in the church’s stained glass windows.

Art produces a world imagined

as it cries out to tell the unseen truths of life and the world,

then perhaps the transformation of day-by-day reality

via artful creation

invents a world which is more real

than the average person’s clouded take of reality.

The raw material of art is found in the events of conscious and unconscious being,

which seem to be surfacing through struggle

in the layers of these charcoal portraits.

Conditions and events constitute everyday struggles,

which also continually form who we become.

To me, this is one of the powerful currents in Auerbach’s work;

the sense of continual transformation in the portraits

as well as his continual search for the actual truth.

As a photographer I have long been conscious

that I am fixing a fragment of the sitter’s personality at 1/250th of a second.

I have always practiced two things while making portraits:

•the first is setting a quiet, still and serious mood for myself and the sitter;

•the second is coaxing decisive moments

in which the thoughts and feelings of the sitter

transform from one moment to another.

One can see it in the eyes as though there is a movie going on behind them.

But, as I learned from the work

of the famous American photographer, Alfred Stieglitz,

a series across years is perhaps a more balanced and beautiful way to picture someone’s complex life.

Auerbach found a way in a single image.

NOTES

Auerbach was a painter of his time

who broke many rules to create something new and exceptionally humane

after the tragedy of World WAR II in which his Jewish parents were murdered

in one of the concentrations camps.

He was able to rise above the pressures to conform

to the new in vogue abstract expressionism, although to be informed by it.

To see a contemporary painter of the same stature go here:

Ricky Romain’s work should be constantly on display in galleries

and sought after by museums.

•I highly recommend Auerbach’s Charcoal Heads exhibition

at the Courtauld Gallery, Somerset House, London until 27 May 2024.

Dear Patrick...I am flattered and taken aback by the kindness and thoughtfulness of your words....very kind. When I was working mostly as a photographer and then a documentary maker I had no idea how my work touched others...Writing my weekly essays is largely the same....the readership sways up and down but is mostly silent so it is a struggle to maintain the sense of duty or accomplishment....so thank you for your comments, they are heartening.

Dear Robert your essays are thought provoking, humane, tough minded and unsentimental. I look forward every Saturday morning to reading your latest offering. Your perceptions do something few writers currently do for me which is tilt the world on its axis a little and nudge me gently but firmly to consider the act of creativity in a wider social and political context. I have nothing but respect and admiration for the way you elucidate the meaning of our creative acts. I always come away feeling emboldened and inspired to do make my own work more truthful and authentic. Thank you. You are very much heard and your words and images make a difference to how I perceive the world.