INTRODUCTION

A friend of mine asked me, “can you consider whether abstract art can be ‘activist’? I’m struggling with this concept - been to Kahlo and Diego immersive exhibition at Canada Water - more than ever we need artists to be activists and speak to the people? How can abstract art do this if it’s unfathomable????”

I have tried to answer.

FIRST ENCOUNTER

I was seventeen. For the first time walking up a staircase in New York’s Museum of Modern Art, as an aspiring photographer, I was seeking the permanent photographic exhibition I longed to see. While I climbed the stairs, I saw in the distance an elongated horizontal on the distant wall, as big as a postage stamp from where I was.

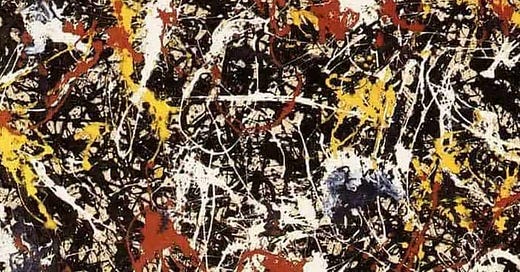

It was an explosion of tangled colours. I was curious as I had never seen anything like it, and it was luring me. I reached the top of the stairs and decided to divert my path from the photographic collection for a moment, allowing myself to be visually seduced by this thing. As I approached it grew to fill my entire sight, increasing my breaths in and out. By the time my nose was a foot from the thick cords of impasto paint, I was electrified by its exciting visual story. My intense responses were from its explosive energy, its complete commitment to what it was, its self-assured sense of demanding to proclaim something - exactly what at that moment - I didn’t know.

This was my second introduction to Jackson Pollock and my first to post World War Two American Abstract Expressionism. Once I noticed the artist’s name, I remembered that I had read books of American history with wonderful drawings of heroic settlers trekking across the vast mid-west, looking for virgin lands to steal, settle and to fence off. In my primary school library, I had been thrilled by Pollock’s realistic detailed drawings which filled my imagination with the grandeur of the American dream. These images were like stills from Hollywood’s imperialist Westerns.

LOSING AND FINDING MEANING

After World War Two it took several years for the America people to recognise the horror of the European holocaust. But as early as 1946, Pollock had changed from that celebrant of Americana to something else. Perhaps it was his recognition of what had happened in the bosom of Germany and other parts of Europe that fostered his rejection of Renaissance naturalism*, and all the tropes of post-World War One European modernism.He painted SHIMMERING SUBSTANCE in 1946. This was Pollock's first completely non-representational works of the Abstract Expressionism.

I believe his response, represented in the painting I saw, was a howl of moral outrage. His athletic application of paint was a physicalized expression of his hatred and disgust with Europe’s disconnected high culture that attended the birth of those totalitarian racist ideas. For him, rationality and Renaissance naturalism was of no further use.

His wild-eyed paintings created abstract art as a commentator on our civilization. For me to respond emotionally was easy. That painting came to me, grasped me by my imagination and forced me to want to know why I so powerfully reacted. To understand it required two things: that I was curious and that I took time to understand it historically and culturally.

Abstraction in art exists on several levels. The first is a distortion of what things look like. Consider the difference between a portrait by, say Rembrandt (below) and one by Picasso in his Cubist period (further below).

The viewer sees the representation of a person in both, but in the Picasso the distortion is so great that it demands an act of imagination to understand why the distortion exists. This makes demands upon the viewer’s openness, tolerance and recognition that they are seeing the artist’s psychological or philosophical response to life which he believes to be of greater importance or interest than showing a more conventional view of a person.

The second is when the painting is completely non-figurative (as the Pollock above), that it does not represent the world as normally perceived by our senses, especially sight. Some people will be open to understanding or indeed positively responding to the work, but many people will not be able to because they have not been introduced to critical or abstract thinking, or in other ways they have been failed by their educational system. This is where the ugly unfairness of class becomes an important issue in the appreciation of art. Class is not just about your skills and pay levels, but also what you can financially and intellectually gain access to.

I was lucky because during my teenage pursuit of becoming a visual artist, I read Clive Bell who introduced me to aesthetics when I was about fifteen. His writing encouraged me to learn more about the intellectual basis of visual arts.

DIFFERENT USES

Returning to the title of this essay, if we bluntly place the value of abstract art in relation to its utilitarian use in promoting progressive social change, we create two problems for ourselves. First, all art cannot and should not be placed in one category because art serves numerous needs in society.

Within communities it brings people together where the process of making is more important that the results. The final work will not be an expression of high artistic merit but rather a sign of the communities wants and needs.

In schools its teaching is about opening children’s minds to abstract thought and to the importance of the imagination and beauty for their lives.

When art is used for exploring as yet unformulated thoughts that are bubbling up in society it becomes prescient (prophetic, revelatory) as does a poem or novel, in that is asks difficult questions which lead people to new perceptions and ideas about themselves and society.

MODERNISM

And finally, in every generation there will be rising young artists who attempt to tackle evolving social/political/cultural problems, those suppressed, as yet unresolved or unacknowledged by the establishment as being important. Often artists will do so as they engage with new levels of knowledge and technology, creating new forms as they examine new problems. This could be a definition of modernism.

The second problem is that the establishment will have had their guardians at the gates of their cultural institutions institutionalized and academicized art which represents their best interests (goals, values and ideologies). Because of this, there is always an attack upon and rejection of the new, especially when it challenges their values.

The up-and-coming generation of artists may produce more cultural peplum, or an art which still inherits modes from Renaissance naturalism, or a new abstraction which struggles with essential social problems of the moment, but in ways that are as yet unresolved, or they may be able to use abstraction in a way that engages the broader public. But the broader public will need a handle to grasp the abstract art’s inner meaning. Context or texts may help but both of these paths may lead towards turning art into propaganda.

An example of a successful effort is Picasso’s painting GUERNICA. The Nazi German and Italian fascist bombing of the Basque country town of Guernica on 26 April, 1937, during the Spanish Civil War of 1936-39, decimated the town in an attempt to terrorize the population. Picasso created what is thought to be the greatest anti-war painting ever. When completed, it was exhibited in the Spanish Republic’s display at the 1937 Paris International Exposition and then travelled around the world. It helped bring worldwide attention to the Spanish Civil War and the all-out war of the fascists against civilians, and afterwards to the horrors of wars everywhere.

Abstract Art, in its various descriptive or non-descriptive forms, may foretell, if we see and hear well, what artists produce, or it may simply be mediocre renditions rehashing the already extant, original works of the past, or, given help from context or texts, it may be understandable and useful for a wider group of people.

It works when groups or classes in a society can grasp its meanings and relevance without having to rely upon ‘experts’ to explain what it means and why it should be embraced. That is when it reflects their needs and wants clearly so that once encountered the art become a metaphor of justice, freedom, unity, solidarity, kindness or sometimes of sacrifice.

*Renaissance naturalism appeared in the mid 14th century with the works of Cimabue, followed by Giotto.

Important discussion Robert. the need for the viewer to spend time contemplating /viewing a piece of work is so important. To view a piece of work that one doesn't really resonate with is so important to understand why and what makes ones own visual vocabulary. I think Guernica is such a brilliant example of abstraction meeting figurative and both still relevant. Sometimes I see it as a work of abstraction other times completely figurative. Not that really matters but it does touch me /humanity on so many levels. Ricky