I was about to start writing this week’s essay

– now a surprise for the future –

when a DHL delivery person interrupted my staring at the blank screen,

fingers hovering over the keyboard.

I eagerly tore, cut, scissored my way into the package

to discover a stunning zine or booklet (in old fashion language).

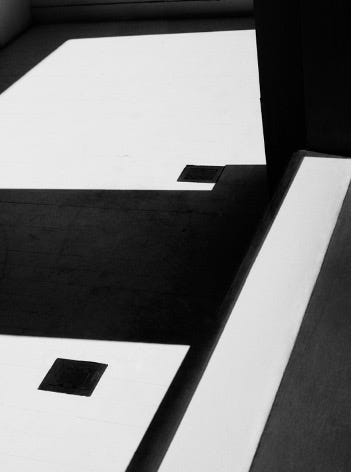

It is a collection of handsome black and white photographs,

entirely urban and graphically compelling,

indeed powerful images.

They are details of signs and walls with the occasional drapery

or wooden flat seen through windows or sheets of glass.

Painted surfaces, peeling materials, stone, plaster, cement, glass

play their rolls in intriguing the viewer.

Reflections play their part in questioning what plane one is seeing

and sun created shadows play their role in describing space and form.

Often these reveal theatrics of highlights and shadows

begging questions of exactly what space one is looking at.

All part of the intricate visual play.

The photographs are by Robin Broadbent,

a New York based English photographer.

I have to admit Robin is an ex-assistant of mine

from my studio days in London,

but he is also a much respected talent

and a much loved younger friend of my wife and me.

He is a unique part of our extended creative family

from around Europe and the States.

The zine stirs rich cultural references.

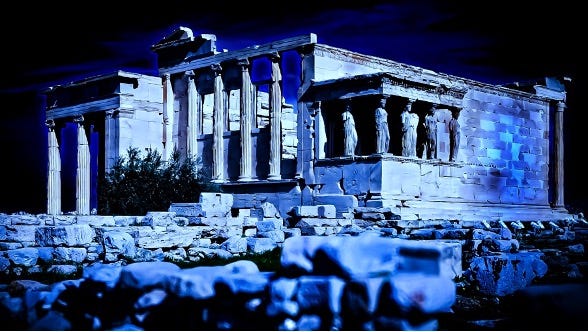

First there is a reminder,

no matter how buried in one’s visual memory,

of ancient Greek temples and other buildings

carved out of the landscape by the brilliant highlights of the white marble columns

and the deep shadows cast by the clear Mediterranean sun.

This kind of work, especially linked to architecture

cannot avoid calling upon one’s admiration

for the post Russian revolutionary Constructivist art of El Lissitzky,

Alexander Rodchenko and others.

Constructivism re-imagined the role of art in society.

Artworks were to be part of a broad social program

made to awaken the masses.

Through the art they would learn of class divisions,

social inequalities, and revolution.

Unfortunately for many of the artists,

they were made to serve the state,

not as artists but as propagandists

illustrating the Communist Party’s ideology.

When they disagreed at this loss of freedom

they were expelled, arrested, disappeared of sent into exile.

But their art, also linked to Picasso’s 3 dimensional cubist work,

wrote a new chapter in European culture.

Whether most of us are consciously aware of it or not,

it is part of our shared visual history.

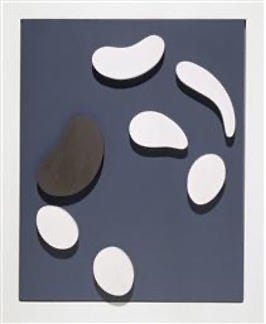

I have a memory of Robin sitting on a couch in our studio reception

studying a book of images.

Something touched me about the visuals I had previously seen of his

so I handed him a book by Jean Arp

who was connected to constructivism

and was influenced by it and by Picasso.

But in a phone call before this being published,

I asked Robin if he remembered the event above.

He said he did, but the book was about the work of Kandinsky

who was influenced by Madame Blavatsky,

a prominent believer in Theosophy.

This was a theory that creation is a geometrical progression,

beginning with a single point which creatively alters form

which is represented by a descending series of circles, triangles, and squares.

In other words, that truth was to be found in pure form.

Perhaps seeing either book had an effect on Robin’s maturing work.

His concern and attention to the use of form and solid blocks of tone or colour

were excited by this introduction.

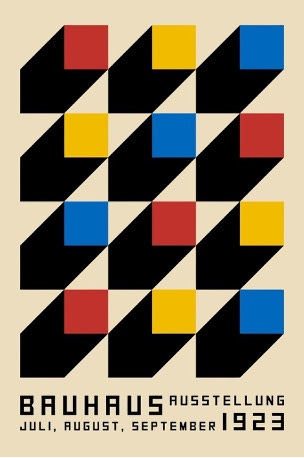

There are also echoes of the Bauhaus

in the reductive compositions of his photographs

which concentrate on modern industrial made materials,

moulded into efficient unadorned load bearing shapes.

The Bauhaus dictum, Less is More is an intrinsic part of the photographed objects

and of the tonalities and compositions of the photographs themselves.

The journey through the zine, designed by Doug Lloyd, is in itself a delight

with its use of repeated images,

its juxtaposition of image against image,

the use of differing sizes from page to page,

and it sudden use of colour,

which is a surprise and a delightful visual joke

well worth a smile.

The collection is called A LOVE LETTER TO.

The unknown recipient may be New York city or perhaps a person unnamed.

With this warm embrace

there is something untouchably sad in the collection.

There may be, as a consequence of Robin’s success in the city,

an endearing sense of belonging and acceptance

which is possibly a one-sided love

from a city often seething with poverty, anger, rebellion

and plain nuttiness.

But I think it is something more fundamental.

I admire the images for their formal, compositional and technical excellence,

I am delighted by the humour

and the exposition of the very sinews of our modern urban environment,

but at the same time his photographs picture emptiness,

the uninviting urban fabric of our questionable humanity.

We see the passing on of corporate interests in the wreaked facades

and the uncared for peeling and otherwise deteriorating materials,

in the rain and snow eroded signs.

Robin’s images tell us about a dream and a slowly dying nightmare

as the American century dwindles in the shadow of totalitarian instincts,

and under the clouds of a collapsing empire.

This is a set of photographs that need to be viewed several times

until one recalls the depth of cultural and political history they reveal.

Truly a lesson in not just seeing but also in looking

in wonder, in hope, in embracing and in rejection,

on the part of both the artist and his audience.

More of Robins work can be seen here.

It is definitely worth a look at.

You will see how he brings the same concentration`

to beautiful light and shadows,

and to the use of tonal scales and colour in his commercial work

as he does to his personal work.

It is where craft crosses to beauty and beauty crosses to true artistry.

Robin is such a talent